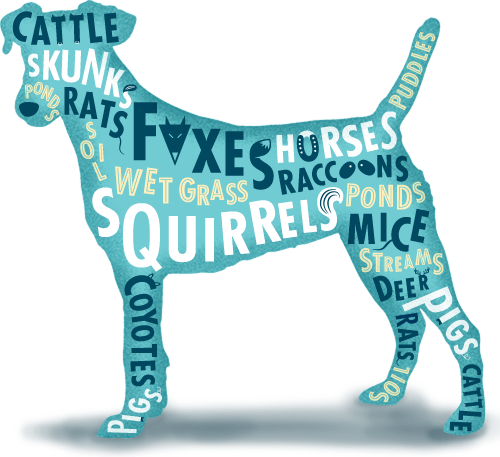

Leptospirosis is a disease caused by the bactera Leptospira. This bacteria is carried by and shed in the urine of many wildlife hosts including skunks, foxes, rats and racoons. In these hosts the bacteria resides within the kidney and causes no clinical signs. Cohabitation with these wild animals is increasing due to suburban growth encroaching on their natural habitat. Thus, it is possible for all dogs, urban and rural alike, to cross paths with Leptospira. Dogs are exposed to the bacteria when they come in contact with water or organic material soiled with urine from an infected animal.

Once inside the dog the bacteria replicates and travels throughout the body in the blood. This allows rapid access to all of the organ systems including the liver, spleen, kidneys, eyes and central nervous system. The wide spread of the bacteria results in the varied clinical signs of leptospirosis. These include, but are not limited to: fever, anorexia, soreness, jaundice, vomiting, diarrhea, depression, weakness and hemorrhages of the mucous membranes.

Basic biochemistry and complete blood count performed when a dog first presents often shows evidence of kidney failure, liver damage, and whole body inflammation. A urinalysis also shows changes associated with kidney damage. The test of choice for definitive diagnosis is called a microscopic agglutination test (MAT). This test is performed by a referral laboratory and is reported as a titre. The titre indicates the magnitude of infection with the bacteria if it is present. Unfortunately, this test can be negative during the first 7-10 days of the disease. Alternative tests include PCR and culture.

All methods of diagnosis do not yield immediate answers and thus treatment is initiated prior to obtaining a diagnosis. The sooner treatment can be initiated the more likely it is that existing tissue damage can be reversed. Hospitalization is required and treatment is comprised of supportive care, targeting clinical signs, and antibiotics. Leptospirosis responds well to appropriate and prompt antibiotic therapy. Prognosis is generally good with survival rates reported as 80-90%. However, dogs may develop chronic kidney failure or chronic active hepatitis.

Measures to prevent leptospirosis infection include: control of rodent population, decrease stagnant water, isolation of infected animals, vaccination. The current vaccination available in North American protects against 4 serovars (variant) of Leptospirosis. Unfortunately, infection with Leptospira can occur in vaccinated dogs if they contact a serovar not present in the vaccine.

Leptospirosis can be transmitted to humans from the urine of infected dogs and wildlife. It is therefore important that humans should wear gloves and wash their hands after being in contact with the urine of an infected dog. Clinical signs in humans include: fever, headache, chills, muscle aches, vomiting, jaundice, red eyes, abdominal pain, diarrhea and rash. More information can be found online from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

October is National Pet Wellness Month. More than likely you visit the doctor and/or dentist at least once a year. Are you doing the same for your pet? Because cats and dogs age quicker than us, taking them to the veterinary hospital once a year is like you going once in five to seven years! October is National Pet Wellness Month (NPWM); celebrate by committing to your furry friends’ health with annual wellness exams. The American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) recommends annual wellness exams at a minimum, and as your pet gets older, AAHA suggests that the frequency of visits should be determined on an individual basis, taking into account the pet’s age, species, breed and environment. Talk to your veterinarian about what is right for you and your pet. So, why take your pet in for a checkup at least once a year; “don’t fix it if it ain’t broke,” right? Wrong. It’s all about prevention! Why do you take your car in every 3,000 miles for an oil change, get a physical exam each year at your own doctor’s office or visit the dentist to have your teeth cleaned every six months? You do it to check on your overall health, catch issues before they become problems and prevent future catastrophes. Your pet shouldn’t be any different. When you go in with your pet for a wellness visit, your veterinarian will request a complete history of your pet’s health. Don’t forget to mention any unusual behavior that you have noticed in your pet, including: Coughing, diarrhea, eating more or less than usual, excessive drinking of water, panting, scratching or urination, vomiting, weight gain or weight loss. Your veterinarian will also want to know about your pet’s daily behavior, including his diet, how much water he drinks and his exercise routine. Your veterinarian may ask: Does your pet have trouble getting up in the morning? Does your pet show signs of weakness or unbalance? Does your pet show an unwillingness to exercise? Depending on where you live, your pet’s lifestyle and age and other factors, your veterinarian may also ask about your pet’s exposure to fleas, ticks, heartworms and intestinal parasites. He or she will develop an individualized treatment and/or preventive plan to address these issues. During a wellness exam, your pet will get a complete “tune-up,” just like you would take your car or bike in for, examined from head to toe. When was the last time you took the four-legged friends in for a checkup? Celebrate NPWM and schedule an exam today!

October is National Pet Wellness Month. More than likely you visit the doctor and/or dentist at least once a year. Are you doing the same for your pet? Because cats and dogs age quicker than us, taking them to the veterinary hospital once a year is like you going once in five to seven years! October is National Pet Wellness Month (NPWM); celebrate by committing to your furry friends’ health with annual wellness exams. The American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) recommends annual wellness exams at a minimum, and as your pet gets older, AAHA suggests that the frequency of visits should be determined on an individual basis, taking into account the pet’s age, species, breed and environment. Talk to your veterinarian about what is right for you and your pet. So, why take your pet in for a checkup at least once a year; “don’t fix it if it ain’t broke,” right? Wrong. It’s all about prevention! Why do you take your car in every 3,000 miles for an oil change, get a physical exam each year at your own doctor’s office or visit the dentist to have your teeth cleaned every six months? You do it to check on your overall health, catch issues before they become problems and prevent future catastrophes. Your pet shouldn’t be any different. When you go in with your pet for a wellness visit, your veterinarian will request a complete history of your pet’s health. Don’t forget to mention any unusual behavior that you have noticed in your pet, including: Coughing, diarrhea, eating more or less than usual, excessive drinking of water, panting, scratching or urination, vomiting, weight gain or weight loss. Your veterinarian will also want to know about your pet’s daily behavior, including his diet, how much water he drinks and his exercise routine. Your veterinarian may ask: Does your pet have trouble getting up in the morning? Does your pet show signs of weakness or unbalance? Does your pet show an unwillingness to exercise? Depending on where you live, your pet’s lifestyle and age and other factors, your veterinarian may also ask about your pet’s exposure to fleas, ticks, heartworms and intestinal parasites. He or she will develop an individualized treatment and/or preventive plan to address these issues. During a wellness exam, your pet will get a complete “tune-up,” just like you would take your car or bike in for, examined from head to toe. When was the last time you took the four-legged friends in for a checkup? Celebrate NPWM and schedule an exam today!

Heartworm, flea and tick season will soon be here and we strongly recommend annual ” heartworm testing “. New test kits now give us information not only about your dog’s heartworm status but 3 tick borne diseases. Ticks are able to transmit Lyme disease, erhlichia and anaplasmosis. Recently veterinarians in the London area are diagnosing Lyme disease in our dogs which indicates that the black-legged tick, which is the only tick capable of transmitting Lyme disease to our dogs as well as us, is in our area. Fortunately, dogs are not as severely affected as humans and may even go unnoticed by their owners. The significance of positive Lyme disease in our dogs is the potential risk of pet owners contacting these ticks on your walks.

Heartworm, flea and tick season will soon be here and we strongly recommend annual ” heartworm testing “. New test kits now give us information not only about your dog’s heartworm status but 3 tick borne diseases. Ticks are able to transmit Lyme disease, erhlichia and anaplasmosis. Recently veterinarians in the London area are diagnosing Lyme disease in our dogs which indicates that the black-legged tick, which is the only tick capable of transmitting Lyme disease to our dogs as well as us, is in our area. Fortunately, dogs are not as severely affected as humans and may even go unnoticed by their owners. The significance of positive Lyme disease in our dogs is the potential risk of pet owners contacting these ticks on your walks.